The Startup And Nobel Prize Winner Building The First GPU Auction Market

OneChronos teamed up with prize-winning economist Paul Milgrom of Auctionomics to develop the world's first financial market for GPU compute. Now comes the hard part.

The Upshot

You can trade electricity, hedging against a future power spike. You can make a buck betting on cocoa production (in which case slowing growth from farmers in the Ivory Coast is the kind of thing you worry about).

But startup founder Kelly Littlepage can’t believe the same financial ability doesn’t currently exist for the commodity underpinning the AI boom: GPU compute.

Graphic processing units, purchased by the thousands, have been called the oil for the AI gold rush. It’s why Nvidia is valued on the public market at more than $4 trillion, why CoreWeave and Equinix are buzzy stocks, and why tech giants like Alphabet, Amazon, Meta and Microsoft have announced plans to invest hundreds of billions in infrastructure. Ample access to compute might even be a deciding factor for elite researchers in the recent AI talent wars.

And yet, unlike oil, you can’t easily trade on future compute prices. You can’t hedge against prices dropping just as a massive data center project comes online.

“GPUs are about to be the largest unhedged corporate asset class on the planet,” says Littlepage, the founder and CEO of OneChronos. “These other markets are hedged down to the penny. And then you have GPUs, which everyone is treating like power and oil, but which fundamentally still is not.”

OneChronos, which went through Y Combinator in 2016 and has raised $80 million-plus from VC firms including Addition, BoxGroup, DCVC, DST Global, Green Visor Capital and 9Yards Capital, has made a name for itself in what it calls ‘smart markets’ – more complex auctions that match buyers and sellers for wonkier, larger transactions. Its alternative trading system (ATS) for trading U.S. equities has reached $6.5 billion in daily volume.

But all of that work, Littlepage says, was just a “beachhead” for this: “the bazaar for the AI agents of the future.”

Don’t just take a startup’s word for it. OneChronos partnered with an under-the-radar, powerful firm in the world of market creation called Auctionomics. Co-founded by Nobel Prize winning economist Paul Milgrom, Auctionomics has “quietly come to dominate the industry of market design,” Axios wrote last year; it’s helped clients save billions of dollars on winning bids.

If they can deliver on their promise to build the first financial marketplace for GPU compute, the implications for startups are significant. Such a market could mean cheaper and more reliable compute access for training runs and academic research; it could also help to efficiently sell back excess capacity, and finance large-scale infrastructure projects.

(After publication, another company, Compute Exchange, reached out to claim it has already conducted its own version of GPU compute auction earlier this year.)

It’s a potentially massive unlock for the growing AI sector, as well as the corporations and financial institutions that interact with it. And it’s not so far-fetched as you might think.

“We’re not completely reinventing the wheel,” Milgrom tells Upstarts. “It’s helping people monetize their inventory, finance their investments, and manage their risk.”

More on how they’re doing it – and why startup founders and investors should be paying attention – below.

Presented by Notion.

Meet your new AI team.

They never miss a deadline. Never forget a detail. Never need coffee breaks.

With Notion AI, every employee gets:

- A personal note-taker for every meeting

- A researcher who finds answers instantly

- An editor who drafts documents in minutes

- A builder who creates custom workflows

Join companies like OpenAI, Ramp, and Vercel who are working smarter with Notion AI.

The upside

While OneChronos uses machine learning in its own smart auctions and has long eyed the potential for an AI market, its efforts to build a new kind of auction for compute kicked off in earnest last year as companies invested heavily in datacenter projects.

A cottage industry has developed around renting GPUs on-demand, from CoreWeave to the hyperscaler companies like Amazon and Google, to newer ‘GPU cloud’ startups like SF Compute, and more recently, Nvidia itself. But buying on such spot markets is often one-sided, simply portioning out an existing supply, or brokered through one party aggregating buyers and sellers.

That can lead to startups and other institutions renting compute that ends up not meeting their storage capacity or network requirements, or signing contracts for GPU access that then get yanked back because a higher bidder shows up in the interim.

And while it’s possible to sell back excess capacity via some of these systems, that’s still dependent on one broker to match up, and doesn’t account for when a business might be simultaneously buying and selling across different time frames and potential prices, Littlepage says.

The ability to hedge on price fluctuations, and to sell futures on upcoming capacity, has played a a major role in the development of other markets. But it hasn’t come into the play with costly data centers like the ones that Anthropic, OpenAI, Meta, X.ai and others are looking to build. Earlier in July, The Wall Street Journal reported on challenges facing an announced $500 billion project involving OpenAI and investor Softbank.

“The dollar amounts are so large that people are hesitant to take big risks, and there’s no way to take small risks,” says Stephen Johnson, OneChronos’ other co-founder. “Why is there a hedging market for every other type of commodity, but not compute? We think a lot of it is just the complexity of the instrument type, and how fast it moves.”

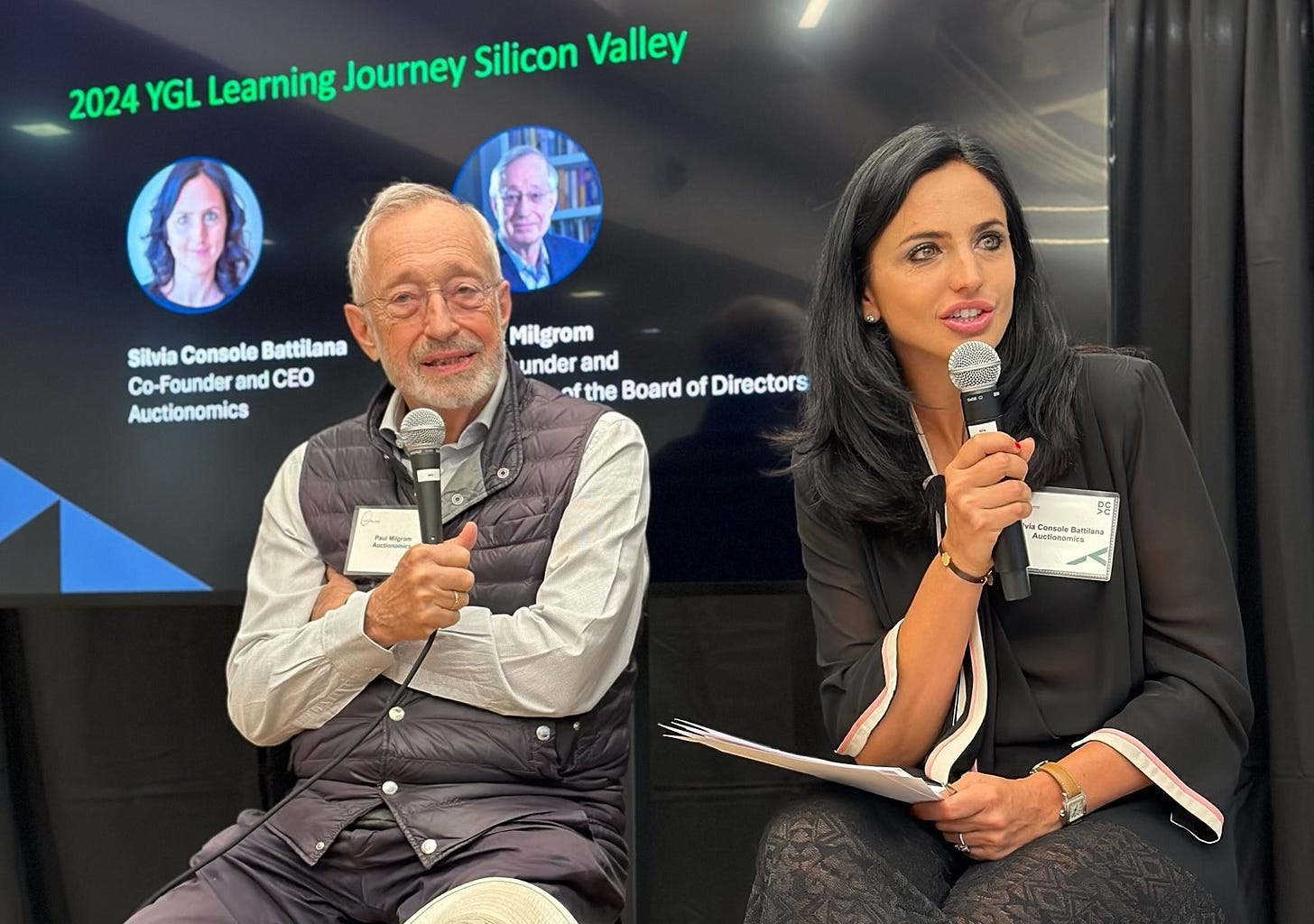

Enter Auctionomics, founded in 2008 by Milgrom, whose work in developing better auctions won him a joint Nobel prize in 2020, and Silvia Console Battilana, a Stanford PhD who had studied game theory and taught at Boccioni University. The duo teamed up to launch Auctionomics in 2008 to help better auction off distressed assets during the financial crisis. In the years since, they’ve set up auction markets and monitored them, and also consulted on others for buyers in Europe, South America, Canada and the U.S.

Auctionomics' interest in GPU computing was natural, its founders say, as the company trains its own language models for each auction project; Milgrom also heard about the challenges of securing GPU access from Stanford colleagues. (He’s also on OneChronos’ scientific advisory board.)

The biggest challenge on the Auctionomics side: creating a mathematical system that can standardize GPU compute in a way that’s easily transactional. Buyers are typically thinking in terms of tokens, whereas sellers are thinking about clusters of GPUs and compute power available across periods of time.

“We spent a lot of our time defining what is exactly for sale,” Console Battilana says. The answer: a building block that Milgrom says he won’t explain in detail, as “part of the magic sauce.”

The uphill battle

For this new system to work, both OneChronos and Auctionomics will need the industry to buy in. That means both parties are already in discussion with a number of stakeholders, from big financial institutions that run data centers, giving them both supply and knowledge of trading futures, to chip owners and manufacturers, and data center operators.

OneChronos declined to name any specific businesses signed on so far. “We think there’s some interest in this from the broad ecosystem, and the more diversity of participants we have, the better and healthier the market will be,” says Johnson.

Their hope is that tech giants like Nvidia and compute startups alike will see their managed GPU compute auctions as another place to trade on inventory, but not a competitor. (Coincidentally, Milgrom recently served as a key witness for Google in its recent U.S. antitrust trial, which iit lost and plans to appeal.)

The ability to resell extra compute capacity on a daily basis, and to lock in future price options from multiple vendors, could help startups and academic institutions better access and manage more limited compute resources, Console Battilana says.

Milgrom is most excited about the potential for a more efficient market to unlock new largescale projects and innovation. He compares this moment in GPUs to the historic wheat market: it wasn’t until railroads enabled grain cars on trains that wheat could truly become tradable at scale, improving food supplies and economic growth.

“Markets evolve and develop new capacities to support new economic activities,” Milgrom says.

It seems inevitable that GPU compute is a market that will be traded as futures sooner than later. There’s seemingly too much money to be made, and too much demand for capacity for something like this system not to take off.

Whether its the OneChronos and Auctionomics marketplace that is the one to pull that off is less certain. They have the credentials and know-how, but they’ll need the bazaar to fill up with people, too – at least until AI agents are managing their own underlying compute.

That puts pressure on its creators to deliver a simple, easy-to-use interface, and solve the chicken-and-egg marketplace problem out of the gate.

“Milgrom has a great quote on this: the best auction is the one that people use,” Littlepage notes.

I had written about the securitization potential of GPU compute last year around this time (https://trees.substack.com/p/thoughts-on-coreweave).

There are differences in interconnects, memory, and type, but GPU compute can be made fungible.

I think the biggest issue is that GPU compute prices tend to trend downward. Oil hedges work since price is so unpredictable in the short term. It can go up or down, so different counter parties "bet" on the direction by providing the hedging instrument. If the price trends downwards continuously, options prices will be way too expensive or the market for it will become illiquid.

Securitization makes sense if you want to create derviative products. If effective supply distribution is an issue, routers like OpenRouter and Martian should be enough.